The Why You Wanna Fly exhibition was produced as part of a participatory action research project that explored the experience of self-stigma and social stigma in the everyday lives of people living with mental illness.

Five people living with mental illness diagnoses (schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety disorders) were engaged as co-researchers to examine and generate knowledge around the experience of stigma. The exhibition also included installations co-created with participants based on transcript data from our discussions and life-story interviews.

The exhibition invited audiences to examine the lived experience of stigma through the participants’ lens. Audiences were invited to consider the part they play in shaping this experience.

Over 9 weeks, the participants took photographs and participated in group discussions through which they recalled periods of their lives when they struggled with mania, hallucinations, delusions, depression, suicide attempts, intense feelings of pain, rejection, frustration, and anger. They traced how meaning-making around mental illness, their life trajectories, and their relationship with medication, their families, intimate partners, and illness and wellness narratives have changed and continue to evolve. Through this work, these brave souls lend us their eyes, their voices, and their hearts and challenge us to use our hands and our voices with what they have gifted us.

What can you do to create compassionate, non-judgmental spaces for people living with mental illness in our communities?

How have you participated in oppressive systems (in your personal and professional spheres) that perpetuate harm for people labeled as mentally ill?

How have your words, actions, and or silences contributed to the lack of emotional safety for non-normative people?

Why you wanna fly? Navigating Mental Illness and Stigma: An immersive arts-based Exhibition

An Overview of the Study

-

Stigma is a significant barrier to a range of aspects related to treating mental illness, including presentation for treatment, access to treatment, and adherence to medication regimes. There are two types of stigma — social stigma and self-stigma. Social stigma results in people with mental illness being judged based on behaviours associated with psychiatric illness rather than who they are as a ‘whole’ being. Self-stigma describes internalised judgment and shame, which contributes to self-isolation and results in low self-esteem and self-efficacy, self-imposed limits on access to treatment resources, poor health outcomes, etc.

-

This research project aimed to generate situated and contextualised knowledge about the experience of living with mental illness. The team used a qualitative method known as photovoice, which entails giving cameras to participants with the objective of taking pictures that depict their experience and perceptions about a given subject matter. Photovoice facilitates social action informed by a partnership between research participants and a researcher or research team in data collection and data analysis.

-

As the research team analyzed the textual and visual data generated, common threads emerged from the participants’ stories. These threads included intense feelings of overwhelm and hopelessness, as well as the palpable pain of being “othered”, ostracized, and cast out in familial and public spaces. We witnessed what appeared to be a struggle with finding ways of visually capturing the answer to the question, “What is stigma?” This led us to ponder the question, what does stigma feel like in the body? We sought to visually capture representations of embodied sensations of self-stigma and social stigma. These representations would make the experience of stigma tangible by visually exploring how participants interacted with social spaces that “othered” them. We also wanted to probe how participants “othered” themselves to grasp more about the experience of self-stigma. This iterative process is an integral part of participatory action research methodology that engages the plan, act, and reflect cycle to drive deliberate action that is responsive to emergent data. Two additional modes of data generation and dissemination became part of the research process: conceptual portraiture and data-driven choreography.

-

Drawing on transcript data of group discussions and life-story interviews, as well as reflective notes, the research team extracted descriptive words and phrases participants used to explore and make meaning of experiences of stigma. These extracts were used to explore what stigma feels like in the body. Building on words and phrases such as defense, flow, creating space, powerlessness, retreat, and surrender, the team explored organic movements to translate these ideas and concepts into five predetermined positions. Choreographed movements were then created around these positions using Nina Simone’s Blackbird for musical accompaniment. Blackbird portrays the experience of being a black woman denoting the pain of being unloved, deserted, and not understood. The weightiness of Simone’s depiction of this experience resonated with the data that emerged from this research project.

-

The Research Team: Tracie Rogers (Principal Investigator), Jason Hunte (Photographer & Psychiatric Nurse), and Karline Brathwaite (Drama Therapist, Choreographer & Dancer).

The Production Team: Tsianne Valere, Shani Agard, and Ayodele La Veau.

Artistic Direction and Support: Kenywn Murray (Visual Artist), Dwayne White Jr (Actor, Theatre Practitioner & Dancer)

Event Management: Anthea Octave, Kimable Rogers and Lydra Chicot

-

Ethics Approval

This PAR project received Institutional Review Board approval from the University of the Southern Caribbean. Informed consent was received from all participants. The Research Team adhered to a rigorous ethical protocol to ensure human rights protections.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The members of the research team have no potential conflicts of interest with respect to this research.

Funding

Disclosure is hereby made of the following financial support for the research:

This project was partially funded by a personal donation from Professor Gerard Hutchinson which was used to purchase cameras for data collection and cover transportation costs for the participants to attend photography training, in-depth interviews, and data analysis sessions. The IRB deemed and approved this amount as non-coercive.

All costs associated with mounting the Exhibition were paid by Dr. Tracie Rogers from her personal funds.

Members of the research and production team did not receive payments of any kind. Participation was completely voluntary.

Conflict of Interests

This research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

-

The Lloyd Best Institute, Carmel Best, Sunity Maharaj, Rawle Gibbons — thank you for facilitating & providing a home for this exhibition.

The Exhibition

-

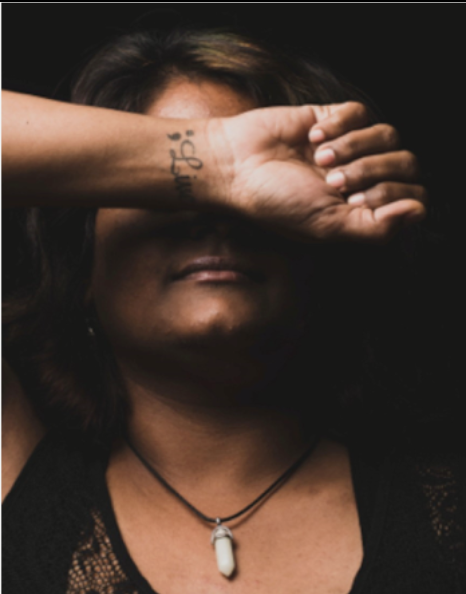

Portraiture

Participants were asked to bring personal items integral to helping them navigate their experience and understanding of stigma. They co-created the artistic design work to finalise the shot while photographer Jason Hunte shot against a black backdrop with a single light source. The artistic design was reflective of their internal sense of how stigma relegates those living with mental illness to dark corners of society.

-

Photovoice

The research team used photovoice, a method that engages participants to collect data about their lived experiences through photography. Photovoice facilitates social action informed by a partnership between research participants and a researcher or research team in data collection and data analysis.

-

The Installations

These installations were created by members of the research team. Each installation was created by one member after several readings of transcripts of life-story interviews conducted by the Principal Investigator.

Portraiture

Talida, who was born in Peru, has been living in Trinidad for the past 3 years with her husband. She was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder about 15 years ago. “My mental health problems started after puberty. I had my first major depressive episode at 14. I was about to be 15 the first time I tried to kill myself. I was somehow still top of my class … I don’t know how. I think that was why nobody noticed until I tried to end it because, “She’s doing well, she’s well adjusted, she’s got good grades. Because that’s all that really matters − she’s performing well.” It was so confusing at first.

“I also had mania. I would not sleep for 5 or 6 days in a row. After many years, and medication I started to manage. Then, for the first time, I had a depressive episode since I was like 17. A full blown depressive episode because there were so many things about Trinidad that were confusing and were not coming up as expected.” In addition to realizing that she would not be able to get residency for many years, being unable to work, experiencing various forms of discrimination because of differences between her ethnic and religious background and that of her husband, Talida also faced challenges with filling medication prescriptions. In recent months, Talida has encountered growing xenophobia and was verbally assaulted by a fellow patron at a restaurant with her husband. Talida’s photographs explore her struggle to be healthy in an environment that feels combative owing to her mental health status and migrant status. Talida is fearful that her mental health will deteriorate if she continues to live in Trinidad.

Defense: As a practitioner of Krav Maga, the military self-defense developed for and used by the Israeli Defense Forces, Talida likened navigating the stigma of mental illness to a sparing match. In this photo, she assumes a basic defensive stance although she later informed the photographer that the first move in Krav Maga is to create space. Creating space allows opportunity for assessing a threat before deciding how to engage.

Split Mind was diagnosed with schizophrenia seven years ago. He is a recording artist and producer and has openly explored living with a mental illness in his music. Split Mind was transferred from a drug rehabilitation center to the public mental hospital where he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Since his diagnosis, Split Mind has committed to a vegan lifestyle and is very cognizant of what fuels his mind and body — he credits his feeling of health and wellness to this significant shift. “I still hear voices in my head, I don’t eat meat and all kinds of things. It’s kind of pleasant, like music to my ears.

“If I’m doing stupidness in my life, it will tell me − it’s good vibes. If they’re too loud, I know that my body is out of balance right now, so I need to organize myself. It’s a guide to me.” Split Mind’s photographs explore his daily encounters, efforts to educate himself and to make and produce music, and the impact of family and social structures on his life. “Thinking back in the time of my past ways; My past days; Am I guilty of some crime. Or just guilty of being me; should I have any reason to feel shame? Just notice of lately I just like being humble; Humble till I’m quiet. Some may ask if he has anything to hide; As if I’m wearing a mask instead of being outspoken and driving a stake. I just hope my truth is something people are willing to take. Words spoken can’t be taken back; Same way time can’t be rewind; So, with these seconds, minutes, hours; These voices in my head, call them split minds; So high until you can’t see me So high as if in a place able to touch the clouds; Looking down, nothing evil to see anything.”

Split Mind: As a recording artist, Split Mind uses his talent to express himself through words and music as a way to navigate stigma. When he is recording or performing, he finds his flow. Nothing can touch or stop him. Split Mind recreates his flow, sharing that, when the mic is in his hand, he feels most powerful.

Smile: “I was diagnosed with being schizophrenic at around 18 or 19. All before, as a child I would hear strange noises and my brothers would laugh at me and say, “That’s the wind blowing through your head.”” Ginger has been living with her diagnosis for more than 15 years and, since that time, she has struggled intensely with social stigma at the hands of some family members and in the workplace. She recently decided to discontinue working. This has been a very difficult decision for her since it goes against what she has been taught a “normal and good person is supposed to do.”

Not being engaged in work has strong negative connotations in Ginger’s family of origin and deciding not to work has been a personal accomplishment: “Last year, after I tried to commit suicide, twice, a [family member] came home one day and saw me home. He said, “What are you doing home?” I looked at him, this was 3 days after. He said, “Why are you not at work?” I said, “Well, I’m not going back to work.” And he said, “I’m telling you, you have to go back to work.” And I said, “And I’m telling you, I’m not going back to work.”” Ginger’s photography explores how she has made meaning of her life despite many years of despair and coming to terms with her diagnosis; she started photography as a way of coping with her illness. “Photography is my way to find and hold the beauty of life.”

Smile: As an avid fan of and hobbyist photographer, Ginger understands how cathartic the process of creating can be. In “Smile” she demonstrates what for her has been her one source of freedom in a world where the stigma of mental illness can force one into a life of dependency.

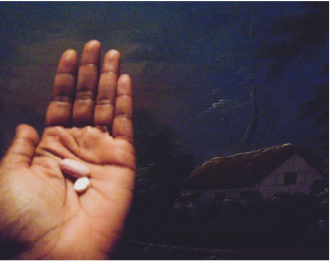

The Advocate: “Elle is a mental health professional and mental health advocate who has been diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder. “Internally, the stigma is in terms of taking medication which is something I still struggle with all the time – it makes me feel weak. Before I got diagnosed I always felt like this strong person. I remember one friend saying that I always seemed to have it together – something would happen and I would just move past it, not sit down and wallow.

“I didn’t deal with my feelings in a healthy way. So now, having to take medication to be able to function normally it’s kind of hard. I feel good when I could function without it – I feel normal. Being surrounded by feelings of incompetence, feeling like a victim, thinking about my childhood, feeling angry… Sometimes as much as, my story is out there, there is still some level of shame associated with it. If I feel like somebody doesn’t know and they find out – even when they say nothing is wrong with me – the person they see is like “you could never have a mental illness”.” Elle’s photography explores being what she calls “a high functioning mentally ill person”. She explores building self-awareness and learning how to manage her illness. “I know me being very hyperactive sometimes is my mental illness – having a flight of ideas. Because I know it, I’m the only one who could identify it and monitor it. I think that crashing and being severely burnt out a lot of times has taught me okay, you need to monitor the things you commit yourself to and try to do one thing at a time. In some ways, I see hyper mania as a super-power but you really have to be able to manage it.”

The Advocate: As a mental health professional and advocate, Elle knows all too well the effect that stigma can have on one’s well being. She uses her knowledge and expertise as a way to go beyond the call of duty and help those in need. This photograph Elle posing with one of her many resource tools in the fight against stigma.

Phoenix is newly diagnosed with depression — it has been one year. For most of her adult life, she has struggled with suicidal thoughts. She has recently tattooed the word “Live” on her wrist, preceded by a semi-colon. The semi-colon reminds her that she can choose to not end her life. This suicide prevention message has become a significant coping strategy for Phoenix. “My internal self is basically based on social stigma. When they see me act a certain way that they don’t deem normal, they decide to say words like, “You are crazy, you are cuckoo”.

“When their harsh words get to me, I tend to believe what they tell me about myself. They say words that hurt more than anything. Sticks and stones… But it’s true, people just don’t know how much their words could attack someone…Someone with, I wouldn’t say a weak mind, but someone who already has doubts. I am shattered and glued.”

Alive: As a poet, Phoenix knows all too well the importance of thought and the spoken word. She reminds herself daily that just being here is a blessing.

Photovoice

Two Thematic Areas were explored: Self Stigma & Social Stigma

Self Stigma

Describes Internalized Judgment and shame; It often results in low self-esteem and self-efficacy. Internalized stigma has been found to contribute to self-isolation, self-imposed limits on access to treatment, or independent living opportunities (Anderson & Warner, 2016; Waston et al, 2007). Studies have found that people with treatment stigma who are diagnosed with mental illness often undermine their course of treatment ultimately and ultimately their quality of life (Corrigan & Watson, 2002; Overton and Medina, 2008).

Contemplating the semi colon. That point between closely related, independent clauses. To live or to die

I started the meds, then the meditation I started all those things that I researched and how to cope with it. A lot of things in my life were really kept back by my own self. My own fear, my own thoughts about myself, I create obstacles for myself and then there’s a lot of people who would see things, and see my potential but maybe I don’t realize, and they try to block me because of that. I’m too blind to see it at that moment.

Shattered and glued Eyes to ceiling Thinking about dying Glorifying death Thinking about finding peace I understand how depression can make things feel But I still feel it All of it

![I used to cry myself [to sleep] at night and I was Puzzled.

Puzzled and confused, and then developed a little difference in my personality.

I used to think I was a boy.

I even named the boy- Nigel.

I would have a boyish way about me, just to prot](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/617bfdd8210b2615fd1a9921/942c976f-dec3-412b-986e-0c3870bdc5a2/jhbjhjbjkb.jpg)

I used to cry myself [to sleep] at night and I was Puzzled. Puzzled and confused, and then developed a little difference in my personality. I used to think I was a boy. I even named the boy- Nigel. I would have a boyish way about me, just to protect myself. People would think I’m crazy for that but, that’s how my mind adapted to the situation that was going on. It was like a safety net. Like you’d fly out, and then it would just catch you and put you back into place. That’s how my mind operates.

I had a suicidal vibe because before I went to rehab I had tripped and cut off my rass with scissors because I was feeling real heavy at the time. I was not using my left hand for anything because I was thinking the left hand is bad. Using my right hand for every single thing at that point in time, I was real chemically imbalanced. I kept asking myself how I come to this.. This kind of mad

“Mental Illness makes you small. It’s like you are living beneath the chaos. That’s what was running through my mind and tried to capture that.

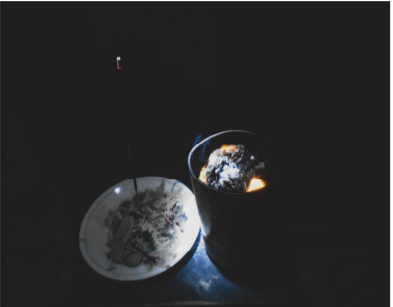

Sick about being sick When things get heavy a good cleaning the only thing that helps. I clean. Turn things inside out and then I burn my incense. Sit in darkness and watch the smoke. Breathe it in. When I feel sick about being sick.I have to sit with the murkiness and wait out the smoke so I can feel clean again.

These shirts could fit before the meds I crawl back into my memory of myself when I could fit into myself

What is the next step for me? Can’t make any step right now But make myself a better person That is what I should do.

Sometimes You don’t want anybody to see you You’re not making eye contact with anybody. You’re looking at the ground, when in reality you’re supposed to keep your head up its like a weight on your shoulder. at that point in time, I didn’t have the skill, or the foresight or knowledge to deal with that So I just avoided people.

Listen up!

Split Mind - Installation

Having to take medication to be able to function normally is kind of hard. It is a constant reminder that something is wrong with you.

Sometimes I’m not in the frame of mind where I want to deal I often feel as though people are judging me in terms of my competence as a helping professional. Feeling, though a lot of times its my own self-inflicted judgments, where I feel inefficient. I feel as though I’m not doing enough- where I may have taken time off because I just can’t cope with the amount of work.

Everything I try to do- I doesn’t work out That’s Hard That’s a hard pill to swallow, knowing that everything you try to do you’re crappy at.

It was twice I tried to commit suicide, and then I realized, “I’m not good at this, so I’m not going to try again.” I went to Mary. Before the labels she was my companion. I looked up I could not come back to being looked at again.

Excerpt from interview transcript used to create the installation:

Woman in a Box - Tracie Rogers

I no longer had psychiatrist, I had to finagle my way into one here. Then there was the problem with the medication shortage because I had to switch to Depakote because the lithium supply here was sporadic, and I couldn’t just live with that unreliability. The first switch was horrible and then I crawled out of it. I went back on just the antidepressants. The first year [in Trinidad] was very dark It was also adapting to things I took for granted, everywhere I lived, walked in the street, taking public transport. Here you had drive or be driven and its too sunny to walk and there are no sidewalks.

Horror and Infestation- Magic Card Eternal Scourge This Eldritch reminds me of the mental illness- Its like a dark part of me that is always ready to jump out during a relapse or depressed day.

Exposed and Scattered. I have grown accustomed to people knowing that I am struggling. I have been falling apart for many years. I feel more exposed when someone knows that I struggle with struggling.

Hope flickers Three There may have been another one I dont think I was really trying to kill myself I just wanted to run away and its so happened that a bridge was in the way, At that point I was more manic than depressed. The kind of low point that gets a 14 year old that’s recognized as successful, smart, accomplished to just not want to live any more.I cants remember how I felt exactly I dont think I want to.

Social Stigma

Often manifests as social exclusion and marginalization, accompanied by disproportionate access to services and disparaging treatment. Overton and Medina (2008) assert that “with a spoiled collective identity, the stigmatized person is reduced in the minds of others from a whole and normal person to a tainted, discounted one.”

When I told someone that I’m schizophrenic and they asked me if I didn’t get the lotto numbers. It’s okay for people to make fun of me, but it’s not okay for me to show that I’m not happy about what you’ve just said to me. It’s always been like that, it’s okay for you to tell me something to hurt my feelings, but when I respond – all of a sudden I’m rude and I’m out of place.

My life is the corner that everyone passes but no one sees. I need to stop. Cause no one else will

I hate the word crazy. I am very sensitive to it. People’s words hurt me. Being classed as crazy hurts me

I think that’s my biggest thing when it comes to external stigma – people not seeing that this is how your mental illness can manifest. They see it as you being lazy and not wanting to show up and do what you have to do. In terms of how it made me feel, it was really bad. It diminished my self-esteem. As a time before, I felt as if working didn’t make any sense to me – I felt incompetent and I had to deal with those comments. I felt like giving up and not working.

I believe in God and his ability to be in my life no matter where I am. What would’ve hindered me would have been the beliefs that I had about who God was and also the whole issue of being demon possessed. That made it a bit more difficult to accept because even in the back of my mind you think that its because you have some sort of spirit in you that you need to be delivered from. Its what I was told.

The biggest challenge for me is that a lot of people think that nothing is wrong with me, so I always get, “Girl… nothing wrong with you!” I’m very high functioning, so they see a high functioning, beautiful, young person, always vibrant and a lot of times they say, “Nothing is wrong with you.” … they don’t see the personal and intricate struggle that I have sometimes. … they think that you’re all together. I hate hearing “nothing is wrong with you”

Some people do not respect my boundaries. I realized that sometimes you really have to be your own advocate. Before I could advocate for anybody else, I really had to advocate for myself because I feel as though we live in society where people really don’t care. That’s my experience sometimes-that people really don’t care

When I was sick there was someone who said some really hurtful things-she asked me if I wanted to be vagrant on road because my mother needs to work and cant watch me all the time I remember I started to get anxious because I was like “You don’t know what the hell going on”

I have a supportive supervisor…he doesnt put pressure on me. I once told him I don’t reach to work early, because I need to psychologically prepare myself before i get there and he’s fine with that. I have to thank God that I have

A Found Poem is created through the use of words found within a given interview transcript. It was used as an analytic approach to thematic analysis.

I feel like people are judging me, not accepting me…. Anything I say or do is not good enough. Basically not getting me, misinterpreting me. I then pull back from showing who I really am to people because of not being accepted sometimes and I just have to push through it for my job and stuff. Though, with being alive you have to push through all those things. its like a fight every day to force myself to actually see people, to greet people. I have to protect myself, to protect my mentality because sometimes it can be so stressful it drives you insane. So maybe its for our own protection we pull back, just don’t like to see people. protecting people protecting me

When I go to another country. The experience of getting away from everybody and sitting down in a place where you’re away from everybody – nobody knows you, nobody could judge. You can express yourself, how crazy you could be without worrying what they think about you because you’re not going to see them in the next 2-3 days

Alot of people don’t look at mental illness like a disability because its not physical you’re not seeing someone walking down the stress walking funny or looking disfigured. That’s what people judge disability by, Its not contagious, so were not making an awareness to make anyone afraid of us, or shy away from us. We just want to show that we are here, and we need to be supported…it is difficult for us to live and be walking around taking part in daily activities. I’m not saying you have to cheer us on but, try and not make things more difficult for some people. You could be the factor that sends someone from 0-100

Forced to accept my past mistakes because there is no other way to move on. Forward is the movement. This split mind shall not be broken by the breakers and the takers

I was working in a school, so I went to the vice principal and I said well this is my issue, I’m schizophrenic. They were like, “wow, oh my God

All of this is me …My father feels ashamed. He says I cant tell people that, you don’t know how it will affect you, your jobs etc. And I was thinking, “Who’s this man boy? Watch what he telling me” I did research and people with schizophrenia, rather the percentage of the population living with schizophrenia is not that high. ! in every 100 persons has it. So I have to laugh Cause I’m like a 1 percenter and that’s how I look at it. I also look at it like when it has so much great things to say about people who have mental illness. I shouldn’t give a rat’s ass about what people think.

There are so many sides of me. They wont guess They cant know Cause all they see is a label

Realizing that I have a choice helped me I have a choice I can make brave choices Not just to survive but just because it makes me happy.

Found Poem